I’ve been pondering Artificial Intelligence, AI, along with just about everyone else in the world and mostly coming up with negative, doomsday scenarios. But this morning, I found the nudge into a more positive place that knit together what I know from my experience schooling youth in an alternative system, my grandchildren’s recent camping trip to the wilds of Algonquin, and the article I read about an afterschool program for youth, the Youth Climate Action Leadership Series.

In the age of AI what do youth need, what do they crave that would make putting effort into learning worthwhile? For some youth, the situation they’ve grown up in or that their parents grew up in clearly indicates to them that they need not onlly academic credentials but also the ‘how to’ to be successful and provide for themselves and their families. And so, they put the attention and effort into truly learning. But for many youth an academic education isn’t a priority, maybe the marks but not the actual learning They attend school because it is expected. They have to.

Developmentally, genetically, adolescents are primed for action, for risk, for learning by doing – just when we confine them to seats in a classroom and prescribe their activities. Ask most high school students about their day and the majority will tell you about anything but their classes. You’ll hear about their friends, what’s happened on social media, how well they’re doing in an online game, perhaps about football or band practice or auditions for the musical – anything and everything but their classes.

In the article about the Youth Climate Action Leadership Series in the Community Foundation of Greater Peterborough’s summer newsletter (the third article), we find one of the keys to what engaged, adolescent education could be. In this programme youth aged 13 to 18 were invited to co-create and lead hands-on workshops on climate action.

“They’re not only working on eco-friendly craft projects while connecting with peers and community members. These young people were given real decision-making power, including how to allocate actual funds to projects that mattered to them.” And that is the key – real decision-making power – agency.

Quotes from the article show the importance and the impact:

“… the real reward was learning how to lead. Not by telling others what to do, but by collaborating.”

“Helping others boosts your sense of self… You can’t get that if you don’t go outside and pitch in.”

“[People] always say that the youth is the future, and here we are, trying to do good and help others. We just need help with it. That’s all we really need. Just more money and support so we can keep doing this.”

“By learning how to mend clothes, reduce waste, and repair electronics, these youth are doing more than gaining practical skills. They are quietly repairing something harder to measure: the frayed threads between generations, between community and climate, between the future they’re inheriting and the world they’re determined to create.”

This is what adolescent education should be.

My grandchildren’s wilderness camping trip had agency and another important component – risk. While my daughter-in-law and the children’s aunt were the responsible adults, everyone needed to work together and contribute. There was no cell service. Each day began with breakfast and group decisions about what they would do and where they would go. Meals to make and tidy up, dishes to be done, fires to be built, canoes to be paddled and portaged. And when I asked them if they were happy to be returning home – no – they would readily have stayed longer. They have camped together for a week each summer for at least 10 years and the other component that has kept them coming back is risk – opportunities to choose to test themselves. Hikes of unknown length and difficulty to spectacular views, cliff jumping into pristine waters, searching for and catching water snakes, surfing rapids, portaging a canoe. “I did it!” Just as the toddler revels in taking their first steps, youth crave testing their limits and discovering they are more than capable.

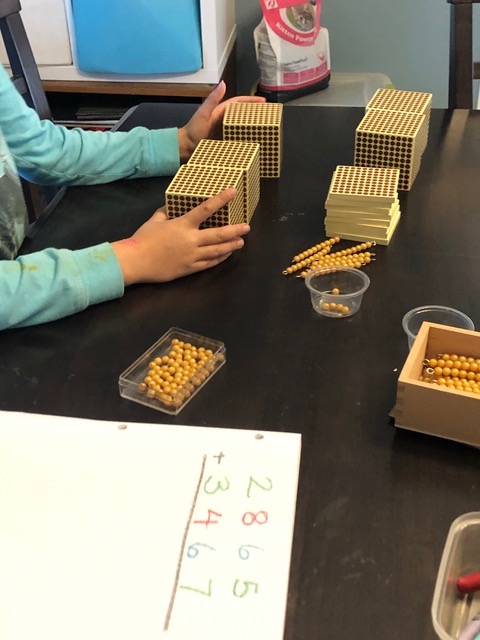

For these reasons, Montessori adolescent programs are organized around such authentic life experiences, originally, and still in some schools, specifically by residing on a farm where all its necessary, real chores and life decisions are placed as fully as possible in the adolescents’ care. The adults act as mentors, coaches and teachers. Academics are linked to the day-to-day requirements of providing for themselves and the farm.

Urban Montessori adolescent programs strive to provide similar experiences of adolescent ownership and responsibility with wilderness trips; work with and for urban organizations like community gardens; and micro-economies – small businesses designed, run and managed by the youth themselves that incorporate the basic concepts of production and exchange. In these urban activities, the adults must exert more self-control so as not to take on responsibilities themselves but rather set up circumstances that place the responsibility and outcomes on the adolescents – succeed or not. On a farm, everyone must work together or the consequences are very real – an animal is in discomfort or the main dinner dish is not ready on time. In urban environments it is much more challenging to place the responsibility on the adolescents, but this is key.

Adolescents are innately designed to be doing and managing and when given the responsibility they not only rise to the task but feel good about themselves and their ability to make authentic contributions.

What does this have to do with Artificial Intelligence? What if schooling set our adolescents to work on the problems of our world? AI could track what each is learning academically as they do this and what each hasn’t yet covered. Perhaps AI could provide lessons individualized and connected to what is currently engaging them. High school buildings could become multi-age community hubs, resource-rich meeting and workspaces – those important third places that our communities are losing, and who knows, new high schools might even have a less penitentiary-like design. Teachers would be mentors, coaches and resources. Imagine having students who want to learn, who want to be involved, who choose to use AI as a tool.

I hope AI will push schooling over the edge into something more compatible with human development, and more useful, exciting, productive, and positive for youth and the world. Given that AI can answer most assigned questions, do research, and complete fully cited essays, we have little choice but to adopt another method of education, another paradigm – a paradigm that capitalizes on the real world and its problems, and includes agency and risk in community with adults who are primed to walk with rather than lecture and direct. It is possible. Yes – it is challenging to change the direction of something as imbedded as our current schooling paradigm but maybe, with an assist and a nudge from AI, it’s possible. Let’s try and see what we’re capable of!

P.S. If you need an assist into feeling more hopeful generally, I highly recommend reading the first article in the Community Foundation of Greater Peterborough’s summer newsletter.

Responses

Does your activity have to involve a challenge in order to experiece flow? Can you experience flow being a Montessori teacher in a classroom or does it only apply to certain kinds of activity? Pat💖Sent from my Galaxy

LikeLike

My understanding is that challenge is necessary for flow. Any kind of activity can create flow – teaching, writing, painting, playing golf, building something.

LikeLike