Concrete materials instead of screens, worksheets or textbooks

Concrete, well-made, open-ended materials that require manipulation have so much more to offer education than textbooks, worksheets, screens or apps, especially in a world with AI. And the younger the student the more imperative their use.

Here’s an example:

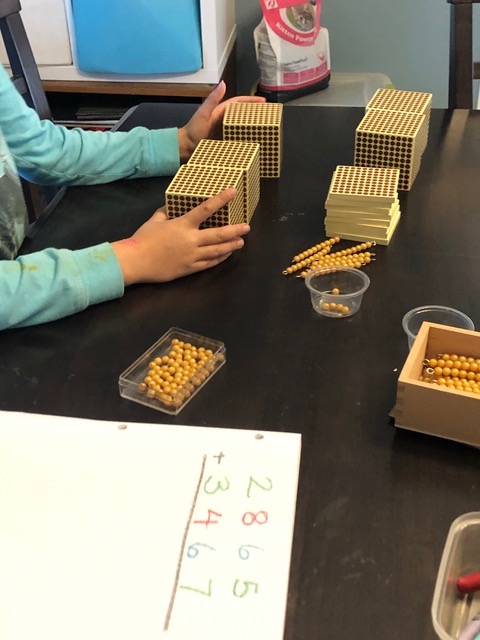

This material is called the Golden Beads. It has unit or one beads, ten bars, hundred squares and thousand cubes, and cards to go with each hierarchy. If you have an elementary-aged child, you’ve probably seen drawings of these on worksheets or in a textbook, but we should provide the material instead of the illustration. Here’s why:

A concrete material-

- Requires movement both large – getting the materials to a mat on the floor where you are going to work, and small – manipulating and organizing the components. (As modern humans we’re often enjoined to move more and so should our children.)

- Combines not only the visual and auditory senses (seeing something and being told the name) but also the physical sense of dimension – how small, large, long, flat, etc.) and the baric sense (the sense of weight)

- Provides the opportunity for working together – cooperating, negotiating, delegating, and sharing information

- Is reusable rather than consumable

- Is shared – requiring taking turns, as well as care and a return to its place so that others may use it (Think beyond the classroom to the reinforcement of ‘Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.’)

- Flexible – can be used for multiple lessons – learning hierarchies and relationships, adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing, borrowing and carrying

- Obvious – students can see the material on a shelf and be reminded that they can work with it

- Open-ended – students can create their own problems to work on. Young elementary students particularly enjoy ‘big’ things, the bigger the better. They can set themselves as large a problem as they want and have the immense satisfaction of solving it ‘Myself!’ At an age when repetition is not highly sought, doing huge problems provides the repetition necessary for consolidation of a concept without requiring an overseer.

- Exploratory – “What happens if each of the three of us take out a quantity of beads without showing the others? Can we figure out who took out the largest number? How much did we take out altogether? How much did we leave on the shelf? How much does our class have when all the material is back in its place?”

- Incremental – One concept leads to another. Learning to count and exchange categories/hierarchies to find how much you have in total before learning to add, learning to add the same addends leading to the concept of multiplication

- Flexible – the speed with which new concepts are introduced can be easily adapted to each student as well as adapting the size or complexity of the problems tackled

- Observable – the teacher can observe students using the material and, without interfering in any way, ascertain whether the concept has been mastered or not, and whether additional instruction is warranted – continuous assessment without tests

- Independent – once a lesson has been given on how to use the beads for a certain task – say adding several quantities of beads together, students can work independently

- More likely to create flow or focused engagement – since an adult is not needed and students are having their needs for independence, movement, socializing and success met as they work, they are more likely to achieve the stage of focused engagement/flow where learning is the most efficient and effort results in renewed energy and feelings of worth and joy.

Why don’t we use concrete materials?

Why don’t we gift our students with multi-sensory, movement-required and thought-required materials that have such open-ended possibilities? It is true that successful use of materials requires a learning environment conducive to student engagement and opportunities for choice. Shouldn’t we be guiding students in making good choices as a life skill? Shouldn’t we be giving students ‘flow’ experiences so that they know the deep joy of engaged activity as an alternative to the addictive, short-lived high of being entertained, even if the entertainment is educational. Shouldn’t we be encouraging the ability to work together?

In addition to a learning environment that provides for using concrete materials, the materials have to be carefully designed in order to be optimally productive. A material should Isolate a concept but be open-ended. The only difference in these beads is how they are arranged – as single, ‘one’ or ‘unit’ beads, in a bar of ten, a square of a hundred or the cube of the thousand. There are no distractions such as cute pictures of animals, flowers or cars, only the beads. The material should be durable and beautiful and be of a size that best fits the students who will use it. Originally these beads were made of glass. Now almost all are plastic but hopefully plastic that has enough weight to give the physical sensation of the difference between the hierarchies. Practical – It isn’t practical to have hundreds and thousands made with beads, so after the concept is introduced most of the hundreds and thousands are wooden representations of the squares and cubes. The material should also be part of a continuum – before the Golden Beads a child would use a number of materials to be introduced to and consolidate the quantities and numerals 1 to 10. After the Golden Beads the learner could use a material that represents the hierarchies with stamps that are the same size but are different colours to represent the different hierarchies, gradually moving the student from the concrete to the abstract. It’s important to see each material as related to what comes before and after, as well as to other disciplines.

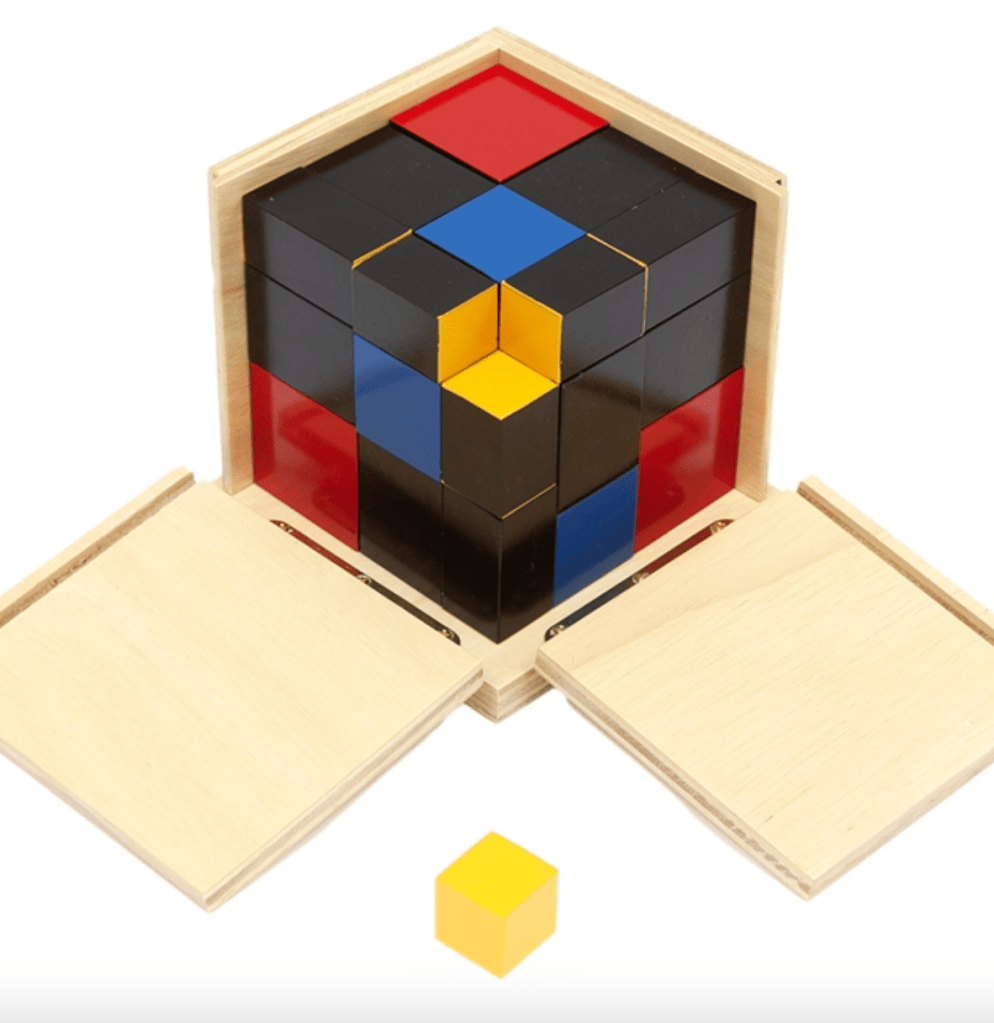

A well-designed material is ageless. When I was taking my Montessori teacher training for 3- to 6-year-olds, we were working with the Trinomial Cube in the stairwell of Victoria College in Toronto. The Trinomial Cube is a physical representation of (x + y + z)3 that is introduced sensorially to children around the age of four as a 3-dimensional puzzle solved by matching colours and shapes. In Elementary classrooms it is used to explore cubing trinomials through assigning numerical values to the variables, and then to explore cubing and finding cube roots – an introduction to algebra. A gentleman passed us going down the stairs, then paused and returned to our landing. Was this what he thought it was? A physical representation of a trinomial? This math prof immediately plopped down on the floor beside us, fascinated.

What were your favourite manipulatives as a youth? Lego, puzzles, building sets, an Easy-Bake oven, carpentry tools, games like ‘Hungry Hippo’ that you had to build first? Chances are they involved movement, possibilities, creation, action and result.

We shouldn’t confine learning to paper and pencil or to the ubiquitous screen. We limit what we and our students can achieve by doing so. Instead, here’s to exploration and learning that engages the hand as a powerful tool of the mind. Here’s to an advantage we have over AI.