What young learners need in a world of AI

There’s a lot out there about AI these days. You can’t peruse any education feed or even scan a news site without running into it. I was pondering what AI can’t give us. And that led to a post on the importance of concrete, hands-on materials for younger children. The younger they are the more imperative activities that involve the hand, movement and the senses as well as the mind. Then thoughts about curriculum. What kind of curriculum do we need in this age of AI and at what age? I think most believe we still need to teach “reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic,” but what about all the other information based curriculum? What do learners need in order to understand history, science, the arts – the information about our world and how we got to where we are? And with that, my mind puzzlingly skipped to a longing for a dusky blue, cloth covered, heavy tome – Odham’s Encyclopedia for Children.

First curriculum – I, along with many others, have fallen in love with the Montessori Elementary curriculum. The first year in a Montessori Elementary class begins with the oral telling of the sweeping story of our universe and our world from the Big Bang through the formation of stars, the happenstance of our solar system, the just rightness of the conditions on Earth, the incremental changes that brought life – single cell organisms, plants, animals and finally us, humans. This story clearly illustrates how everything is connected to everything else, to the past and to what will come. The story is told dramatically, with props, activities and illustrations. There are follow-up activities that sit on the shelves of the classroom for students to use independently to further their exploration. This story is told at the beginning of every school year, Grades One through Six, developing in complexity. It provides a framework into which all other knowledge links and is given meaning.

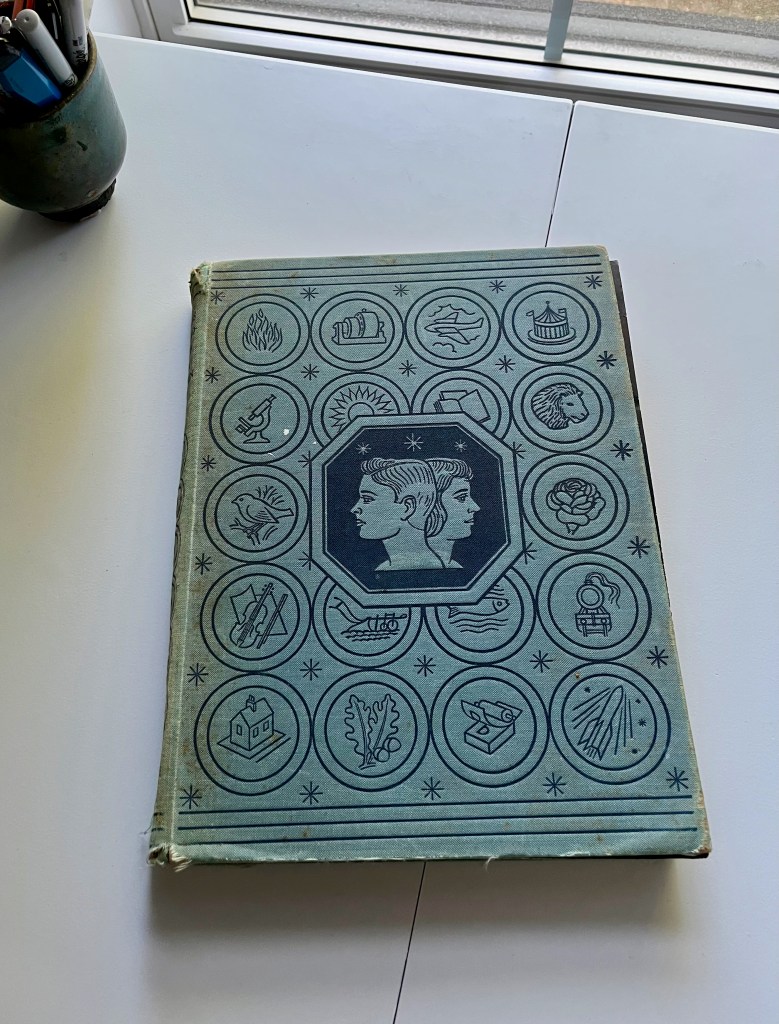

What has that got to do with an old (and I will definitely age myself here) well-used, and loved, children’s encyclopedia. I was surprised when, as I pondered curriculum, it came to mind, especially with the emotional resonance it brought. I had moved across the province about a year ago and had carefully culled my books because books are heavy and cost a lot to move. When I thought I had left this book behind – donated it to a Goodwill store? Gave it to my son for my grandchildren to possibly use as he had? – I was bereft. It surprised me. Why did it matter that I couldn’t lay my hands on this book? I thought about what was in it and considered, for the first time, why it mattered, what it had meant to me.

First came some images – a blue line drawing of a castle spread across two pages with the keep cut away, parts labelled. Then a full colour page of flowers done in watercolour. This encyclopedia was rich with drawings and text. No photographs, mostly black and white or monochrome drawings with some full pages in colour. It was published by a British press in 1957-58. I probably received it when I was 8 and in Grade 3. I think its significance was that it was my window to the world, past and present. I was the oldest of 5, eventually 7, children in a working class, suburban family where there was always something to eat for every meal but not much extra. Neither of my parents had more than some high school; both were of British immigrant families finding their way. We didn’t travel much, certainly not outside of Ontario, or mingle with those who did. A pretty circumscribed upbringing, except for this book.

I found it tucked at the end of one of my bookcases. I had followed my heart and brought it along. In addition to delighting in the many images I had forgotten were there, particularly the continent maps with their illustrations of fauna and raw materials, and a full page of flags of the world, I took a more detailed, nuanced look, reading the editors’ notes for the first time.

This is an encyclopedia, a sort of Aladdin’s cave stuffed, not with jewels, but with facts, more marvelous than jewels and often no less precious. It is a book of knowledge – knowledge of ourselves and our history; of the universe and the world in which we live; knowledge of flowers and animals; of the things we do and use; of science and invention; of the arts; of what is familiar, and what is strange and distant.

Most encyclopedias rely mainly on words to convey knowledge. But this is an encyclopedia in which words and pictures are of almost equal importance. The result is an absorbing display. The world and its wonders become the show of shows.

Yet the display is systematic. The book does not dart from one subject to another so filling your mind with odd scraps of information but deals with each group of allied things often showing in its detailed arrangement how one thing is linked to another. So you can either read it section by section or browse in it, reading here and there as you please.

And here is the thing – I was still being pulled into the content. Even now as I write this with Odham’s beside me, I find myself first slipping through the illustrations and then stopping to read a paragraph about the Romans and soon I was reading through the Middle Ages, Dark Ages, Renaissance and into the Modern Age. The power of this book remains. Why?

It tells a story – with pictures and words. Like any great story it leads you on and in – What happened next? Why? “The world and its wonders become the show of shows.” Knowledge-wise it provides a simplified framework of linked information, enough to whet the appetite for more. It doesn’t provide all the answers. It’s like an open hill in the middle of a countryside. You can see the paths and where they lead and choose which one you want to explore. You can always come back to the hill to see where else you might want to go. A place for curiosity to begin its journey.

What led me from musing about curriculum to an old encyclopedia? Both were windows to the world, a world often beyond my experience. Both provided frameworks that organized how things were connected through time and with one another. Both provided some information – a Goldilocks approach – not too much, not too little, just the right amount. Both were always available – the encyclopedia always present physically (even now) and the curriculum available through the memories created by repetition and the availability of the follow-up activities. Both were rich in words and images, words and images that, again, didn’t tell it all but invited further exploration.

Maybe this is what children need in the age of AI – a physical book, a weighty tome, with just the right amount of information in words and images. One sitting waiting when they are ‘bored’ and they’ve run out of ‘screen time,’ or (better) haven’t been allowed any because we’ve become much more circumspect about allowing young children access to screens and AI access to our children. Maybe this is supplemented by learner-centred schooling that provides a framework approach to knowledge, a framework that opens the world and its wonders for exploration. What path will a child take from these hilltops of curiosity?

Did you have a hilltop like the encyclopedia or the curriculum? What inspired your curiosity? What helped you organize the world and its wonders? I’d love to know, especially from those of you with the view of a different generation than my own. Thanks in advance for your response.

Discover more from Convening Education Change

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

👏👏👏👏Sent from my Galaxy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Pat, This is a beautiful article- I forwarded it to my sister whose kids attended Montessori schools in Toronto years ago. Has this gone to everyone in our Meeting or would you like me to send it around? Mary

–Encore Editing Copy editing, proofreading, fact checking & research Specialty: medical editing 705-872-6557 conchelos@gmail.com LinkedIn: http://ca.linkedin.com/in/mconchelos/

LikeLike